Saline County and Pulaski County are currently bracing for the impacts of a law regulating books found in their libraries.

Act 372 was passed in the Arkansas Legislature this year. The law requires books deemed “harmful to children” to be in a separate restricted section of the library. The law doesn’t go into effect until August, but in the meantime, the Saline County Quorum Court is debating an ordinance telling libraries to “proactively take steps” to relocate certain content.

A Saline County Library board meeting last May turned into an emotional debate over relocating certain books available to children and young adults. At the next board meeting, debate ensued over a policy to allow county judges to make relocation decisions.

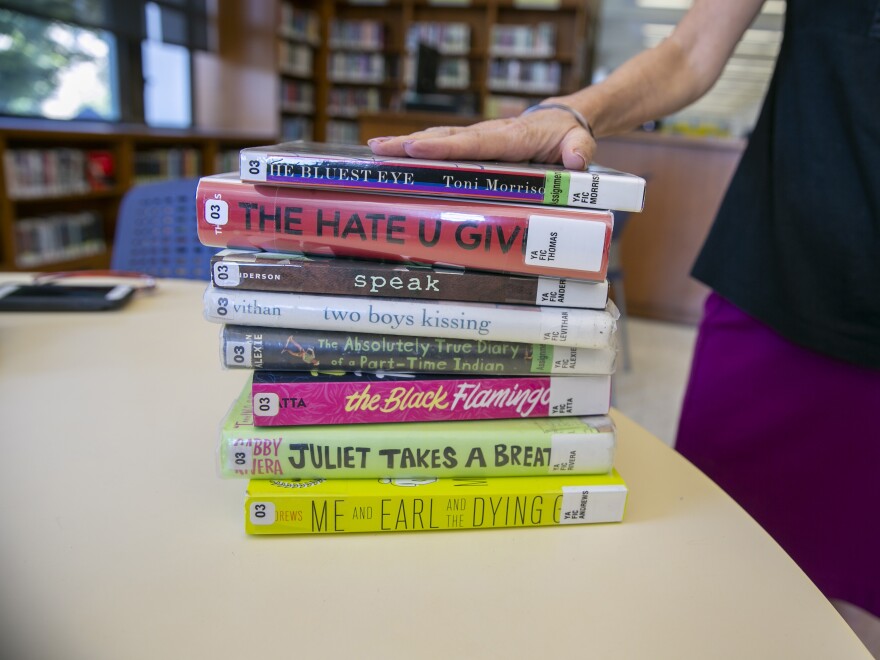

Community members and representatives from the Saline County Republicans spoke out against books they found in the young adult section. Community member Anne Gardner cited a sex education book called “Sex Is a Funny Word” which is available to minors.

“On page 151, this book introduces words in big letters,” she said. “Bisexual, gay, lesbian, queer, asexual. If somebody wants to view this over the age of 18, let them if you must. But don’t leave it out like it's something special. It's not.”

Speaking against the new policy, former Saline County librarian Jordan Reynolds said she loved working at the library, and that books containing LGBTQ themes could bring comfort and acceptance to young members of the community.

“The resolution is saying that these kids, though they are different than us, they're different than our straight white community, that if they don't find themselves in books, it's because they are immoral, perverse and disgusting,” she said.

Kenny Wallis is a community member who regularly live streams library board meetings on the Saline County Republicans Facebook page. He joins many others who believe that relocating books is not the same thing as banning them.

“The first thing I thought of was gas stations, you know they have beer and cigarettes and they put them in an area that's off limits” he said. “They should be able to do something similar with books.”

When reminded that alcohol is not in the first amendment, Wallis responded.

“Yeah, free speech is, but of course, there [are] some limits to free speech.”

There is some court precedent arguing that relocating and banning books are the same thing. Library Director Patty Hector tried to explain her views on this during a recent board meeting.

“Relocating books is the same as banning," she said, met by audible dissent from the public.

In Saline County, a formal challenge process exists for people wanting to remove a certain book from the library. Anyone challenging a book must first meet with the library director, then fill out a complaint form, and present their challenge to a committee. During this entire process, the book stays available in the library.

One of the most controversial books at the library is a memoir called "All Boys Aren’t Blue" by George M. Johnson. It contains LGBTQ themes and some descriptions of sexual activities. Hector recently started reading it.

“It's heartbreaking. It was on the New York Times bestseller list,” she said. “It won an award in Arkansas, which is why we bought it. We buy every award-winning book. It sat on the shelves, it got read maybe three times until they started challenging it. And now it has so many checkouts that it won't get weeded.”

Weeding is the process where out-of-date books or those not being checked out of the library are removed or relocated to the library bookstore. By the time of the May meeting, Hector said none of the mentioned books had been submitted through the formal challenge process.

Attorney Brian Meadors is currently suing Crawford County over their similar decision to relocate children's books containing LGBTQ themes. He says these book removal and relocation policies are allowing a vocal minority to dictate the materials available to everyone.

“Because this particular person doesn't like the book, now everyone is burdened with the additional administrative controls or outright banning that happen as a result of that. And that's called a 'hecklers veto.' First Amendment law is very clear that you can’t have a hecklers veto,” he said.

As debate continues, members of the Saline County Republicans have set up billboards adorned with the phrase “X-rated library books.” The billboard directs onlookers to the website salinelibrary.com which sounds similar to the official library website salinecountylibrary.org. Last month, a counter billboard was put up which says “Stand With The Library.”

Meanwhile, the Central Arkansas Library System is suing to stop Act 372. CALS attorney John Adams said the suit will be brought by a diverse group of patrons and supporters, including a 17-year-old high school student.

Under the law, librarians who allow minors to access books deemed harmful to children could be held criminally liable. CALS executive director Nate Coulter says it's difficult for librarians to work under these constraints.

“People live with uncertainty in the law, for a while,” he said. “But if you are living with uncertainty and there is this criminal sword hanging over you, that uncertainty is untenable.”

Coulter and the other members of the CALS library board pushing for the suit say they simply want clarification on which books are harmful to minors and want to protect librarians from facing criminal penalties.

In an email, Coulter called Act 372: “a horrible bill reflecting an impulse to censor books.”

Alexis Sims was the lone CALS board member to vote against moving forward with the lawsuit.

“I remember as a child going to Hastings,” she said, referring to a now-defunct retail chain. “'Playboy' had black over the cover that’s covering up the obscene and moving it out of the purview of minors.”

At CALS, a child must be 11 to be in the library by themselves. But Sims is reiterating a concern held by those who support the polices. She says many children come to the library alone after school, and wants to prevent them from stumbling upon offensive material.

“I don't think they have that available,” she said. “But there are books that are marketed toward young adults and in the young adult section that explicitly detail sexual acts and obscene things.”

Librarians across the state say there is no obscenity in public libraries. Attorney Brian Meadors explains obscenity is a legal term which only applies to a small amount of content which is “beyond the pale.”

“There is a legal standard for obscenity, and it’s like really strong,” he said. “We're not talking about Playboys or Hustlers or things of that nature.”

Back in Saline County, Patty Hector says challenges to books will not stop her from moving forward.

“I'm just going to keep doing my job. We represent everyone in this community,” she said. “We are not going to let someone who won't even come talk to me or turn in a reconsideration form about a book they have a problem with, dictate what I do in my library.”