Arkansas prison leaders are facing renewed scrutiny over a widely publicized prison escape.

In May, inmate Grant Hardin easily walked out of prison. He was serving a decades-long sentence at the North Central Unit near Calico Rock.

On Monday, the state released more than 900 pages documenting an internal investigation into the incident. The investigation is comprehensive – over 100 inmates and 80 staff members were interviewed, including Hardin, who was interviewed five times. Senior Special Agent Mike McNeill with the Arkansas State Police put the report together.

The final documents describe a chain of mistakes across the prison system before, during and after the escape. Hardin, a former police chief, was wrongly classified as a medium risk inmate, though he was in prison for rape and murder. Hardin was left unsupervised on a loading dock by several prison employees, he was twice buzzed out of the prison gates by accident, and the notification system resulted in a communication breakdown.

At a legislative hearing Tuesday, lawmakers from both parties were skeptical the Department of Corrections had fixed the problems leading to the escape.

The department has generally blamed two employees for the escape, positioning them as bad apples in an otherwise good system. But during the meeting, Division of Correction Director Dexter Payne said three employees have been fired over the escape, and hedged over whether higher-ups should follow.

Sen. Ben Gilmore, R-Crossett, spent large sections of the hearing cross examining Payne, an activity he compared to “going in circles.”

“At some point there are failures beyond human error,” Gilmore said, asking if more should be done than firing people higher on the “food chain.”

“If we don't have the proper oversight to make sure orders are followed, then we can keep playing the circular reasoning game.”

Sen. Andrew Collins, D-Little Rock, made a similar point.

“I feel like I hear you guys acknowledging over and over that it's more than just two people,” he said.

Pointing at comments made by Payne throughout the hearing, Collins said:

“You’re saying without saying, there's more than two people.”

Classification breakdown

Grant Hardin was a violent offender. He pleaded guilty to two felonies and was even the subject of an HBO true crime documentary called “Devil in the Ozarks.”

Before his arrest and incarceration, Hardin was the police chief of Gateway – a small town in the northeast corner of the state. In the documentary, his family described his leadership as frightening, riddled with abuse of power accusations and ending with him being forced out of the role.

In 2017, he was arrested for killing a municipal water employee he allegedly disliked. As is customary after arrests, the police ran Hardin's DNA through a database. They got a match – his DNA matched fluids recovered from an unsolved rape from 1997.

In 2019, he was given an 80-year sentence. Considering his age, it's unlikely he would ever get out of prison.

The prison however, did not classify Hardin as violent.

Arkansas corrections facilities use a point system to characterize inmates and assign privileges. Inmates are either C-2, C-3, C-4, or C-5. The state prison handbook says higher numbers mean more security. Hardin had 26 points, so he was classified as a C-3, medium security. The agency report says he should have been a C-5, supermax or the highest security unit.

The report attributes his misclassification to issues with the prison computer software. The system didn’t catch the timing of both his rape and murder convictions, so points were added for only one of his crimes.

At a legislative meeting in July, prison officials avoided discussing the classification mistake. Hardin had a bad rap sheet compared to other prisoners at the North Central Unit; most were serving shorter sentences for less violent crimes.

Officials said, though his crimes were serious, Hardin didn't stand out or cause trouble in the general population.

“He had been — I'm not going to say a role model inmate, because I don't want to use that term, but he had followed the rules,” North Central Unit Warden Thomas Hurst said.

In prison, Hardin seemed mostly to communicate with his sister, Natalie Hall. Electronic messages give few specifics on prison life, and say nothing about Hardin's crimes or escape plan.

The siblings talk mostly about religion. Hall sent her brother a book called “The Case for Christ,” and they both share Bible verses with each other. Hardin says while locked up, he enjoys listening to John Prine's cover of “In The Garden,” a well known Christian hymn. Hall recommends he try listening to Christian rock singer Zach Williams.

Both like reading books by historian Barbara Tuchman. In prison, Hardin says he read her book “The March of Folly,” and Hall offered to send him other books by the author.

Hall makes several comments about their diverging political views – he's a supporter of President Donald Trump, she's scared of him. Despite that, Hardin never responds to her jabs at the president.

The siblings both reference having respiratory issues that require a CPAP machine. But, the specific medical conditions are redacted in the documents.

Supervision breakdown

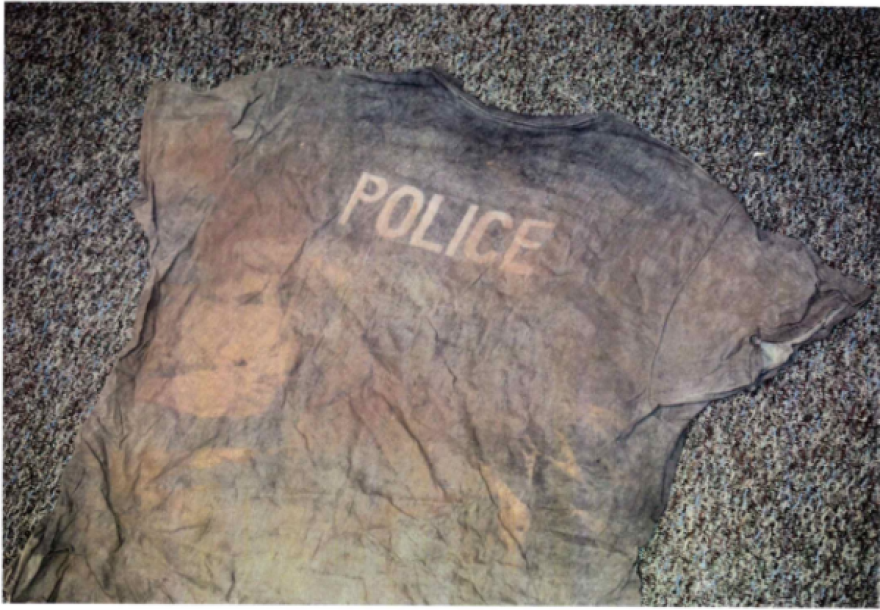

The investigation says Hardin spent six months planning to escape from the North Central Unit. He collected black sharpies “lying around” at his prison kitchen job, and started scribbling black ink into his clothes. He used aprons to make a fake employee vest.

Plan A was to impersonate a staff member and slip out. Plan B was to use cardboard and wood p

allets to make a ladder to climb out of the prison. He prepped for both, collecting cardboard for the day of the exit. He didn't end up needing it.

During repeated interviews, Hardin told the same story to investigators, save for one detail. He vacillated on the exact location in the prison where he colored his clothes black.

In one story, he colored them in his sleeping area. North Central Unit inmates sleep in 60-bed barracks, and shower in groups. Investigators say it's hard to imagine Hardin was able to make an obvious police uniform in a crowded prison without anyone else noticing.

His other claim is that he crafted his costume in the kitchen. This is more in keeping with the evidence found at the scene.

Hardin says he noticed that a trash can in the prison kitchen never was “shaken down” or inspected, though the four staff supervisors of the kitchen were responsible for regular checks. Hardin put his contraband under the trash bag in the bin, something only discovered the day after he escaped.

Prison officials say kitchen workers left prisoners on the back dock unsupervised in the months before the escape. It's unclear if the same employees believed this violated prison rules.

Warden Hurst said after catching inmates left alone outside the kitchen, he gave employees a “verbal directive.”

This may have been the wrong call.

“This verbal directive,” the report said, “directly contradicted the standing NCU Post Orders.”

The report says that some prisoners could be allowed on the dock for cleaning, per prison rules.

Employees seem confused about the policy. In the investigation, virtually every worker has a different interpretation of the rules, even workers within the same department.

The dock was discussed at a May staff meeting, and documented in a report from the meeting. The report only says “Back dock is to stay locked when supervisor is not present.”

Accounts of exactly what was said vary among staff.

Food production supervisor Gregory Woolsey said he remembered being told that some prisoners could be left on the dock alone. Food service staffer Jessica Kanani “recalled being instructed unequivocally that inmates were not to be left unsupervised on the back dock under any circumstances.”

Kitchen supervisor Justin Delvalle made the call to leave Hardin outside alone. Delvalle told investigators he did not think this was a rule violation, or remember it being conveyed that way in a staff meeting.

Warden Hurst said Delvalle “signed a document explicitly prohibiting inmates from being unsupervised on the back dock.”

In any event, Delvalle released Hardin at 2:10 p.m. to clean an outdoor cage.

A lot of the blame for the incident has gone to Sgt. Hayden Grady. He was the food production manager on the day of the escape, and purportedly spent most of the day on his phone.

When asked by an investigator why he was on the phone, the report says Grady was talking to his girlfriend “almost every hour."

Grady was generally cagey during his investigative interview. When asked about Hardin being alone on the back dock, he said:

“I don’t know. I don’t want to say anything that’s going to get me in trouble, so I’d say no comment on that.”

Grady was one of the employees who lost their job.

The realization that Hardin was missing happened at 3:08 p.m. Delvalle went to the dock to get Hardin for dinner. He was gone.

“I hollered his name and I heard no response,” Delvalle said. “I went outside on the back dock to the cage and he was not there.”

Hardin was reported missing about 10 minutes later.

Security footage had a blind spot on the back dock cameras, meaning Hardin was able to easily put on his costume with no one watching him. Hardin brought with him a cart of materials in a rolling dolly to make a ladder if he wasn't let out of the fence.

Fence breakdown

To get out of the prison, Hardin had to slide out of two gates that flanked the perimeter. This part was easy. Hardin simply asked the on-duty tower operator to open the gate.

That officer was William Walker. From the tower, Walker thought he saw a uniformed officer leaving the property.

“I was not paying attention,” he told investigators.”[I] was looking towards the back part of the prison watching it rain.”

The decision to let Hardin through violated prison protocol. Opening the gate is supposed to be a multistep process with a visual identification. But, Walker trusted the man was a staff member.

“I made a huge mistake,” he said. “This all happened because I was complacent and just not paying attention. I never had a plan to help this guy out, and I don’t even give inmates an extra bar of soap.”

Hardin yelled “gate,” which Hurst said is the same way prison employees ask him to open the fence.

In the minutes after he buzzed Hardin through, Walker started to feel uneasy. Hardin left behind his cart with the makeshift ladder. He hadn't gotten in a car and seemed to disappear into the woods.

Walker “hollered” to him, but got no response. He contacted the laundry officer, who didn't think there was a guard matching his timing and description.

Walker started letting other people at the prison know he had made a terrible mistake.

Protocol breakdown

Hardin was out of prison, but the hunt was about to begin.

In the first few minutes, Hardin crossed the road around the facility. He followed a small trail into the woods. This would line up with the track marks searchers later found near the prison.

Meanwhile, employees at the North Central Unit were starting to double check their work. They initiated an emergency count of every prisoner. Everyone was accounted for, except for Hardin.

This is around 3 p.m. on May 25. They didn't find him for another 12 days.

The prison used an “Escape Notification Checklist,” a step-by-step protocol telling employees who to notify first. For some reason, the checklist wasn't fully filled out. Walker, the tower operator, was pulled off duty by a captain, and the replacement did not finish following through on the list.

This means law enforcement agencies were not contacted properly, or in the right order.

By 5:30 p.m., the state and local police had arrived, and were pulling out all the stops to find Hardin.

They put drones in the sky and searchers on the ground. They roamed the land for Hardin using a K-9 named Gracie. They tried using a helicopter to find Hardin, but rain canceled this plan.

The first night Hardin says he didn't move, isolating somewhere in the woods. Hardin started to move around more the second night, but was separated from the food he brought by the law enforcement presence. Instead, he ate off the land, scavenging the wild, eating “berries, bird eggs and ants.”

Police didn't stop looking even in the early hours of the morning. There were sightings, found footprints and leads for six days. Some, like tips that Hardin was in North Dakota, appeared obviously false, but other sightings of him near the prison may have been accurate.

Because he had a CPAP machine, Hardin had been given special distilled water by the prison. He hydrated for twelve days using both distilled water and a nearby creek.

Hardin said his escape plan was to stay hidden in the woods, “for six months if need be.”

He was able to hide because of the rain and vegetation by the prison. The North Central Unit is surrounded by dense wooded areas.

But as he got hungrier, Hardin wondered if he should try to leave the area.

This is how he was caught. A border patrol agent found him when he was on the move. It was 3:28 p.m., June 6. He was one-and-a-half miles from the prison.

Later developments

The day he was caught, Hardin was moved to Varner, a supermax prison in Gould, with much tighter and more oppressive security.

Now, he's facing more charges for felony escape, and has retained the services of defense attorney Bill James. It's highly unlikely he leaves prison again in his lifetime.

Lawmakers have expressed skepticism that prison officials have learned from the mistakes.

“We run as tight of a ship as we can,” Board of Corrections Chair Benny Magness said back in July. He claimed that the “stars aligned” to create the conditions for the escape, and that systemic forces were not at play.

When Warden Hurst testified in front of the committee, he walked that back, admitting he couldn't rule out systemic factors as a partial blame for the mistake.

At the second hearing Tuesday, lawmakers said the investigation showed a web of failures, and not “just two employees.”

“I stand on those two individuals as being responsible for the escape,” Director Payne said. Though he did admit the prison had “policy issues.”

Most lawmakers didn't have time to read the full report, in the roughly 24 hours since they got it. They promised more hearings will happen to discuss the results of the investigation.